Module 6.1

Logistic Regression

Overview

In this module, we will learn about logistic regression, which is a type of regression analysis used to model binary outcomes. Logistic regression is used when the dependent variable is a binary variable (0/1, Yes/No, True/False). Logistic regression is a type of generalized linear model (GLM) that uses the logistic function to model the relationship between the dependent variable and one or more independent variables. Logistic regression is widely used in many fields, including epidemiology, economics, and political science, to model binary outcomes.

Here is a great video by Andrew Ng to get you started with the basic intuition behind logistic regression:

Binary Outcomes

So far, we have looked at continuous or numerical outcomes (response variables). We are often also interested in outcome variables that are binary (Yes/No, or 1/0). For example, did violence happen, or not? Does a country have judicial review? Did a country vote for a particular resolution in the UN?

In order to model binary outcomes, we need to use a different type of regression model called logistic regression. Logistic regression is used to model the probability of a certain class or event existing such as pass/fail, win/lose, alive/dead or healthy/sick. Sometimes you will see analysts using OLS to model binary outcomes, but this is not usually the most appropriate choice. For a number of reasons, logistic regression is a better choice, including the fact that the predicted values are probabilities (which are always between 0 and 1) and the model is more robust to violations of the assumptions of OLS regression.

When modeling binary outcomes, we can think of the outcome as a Bernoulli trial. A Bernoulli trial is a random experiment with exactly two possible outcomes, “success” and “failure”, in which the probability of success is the same every time the experiment is conducted. Success is usually coded as 1, failure as 0. So, ironically, something like conflict onset is a “success” in this context.

Each Bernoulli trial can have a separate probability of success

\[ y_i ∼ Bern(p) \]

We can then use the predictor variables to model that probability of success, \(p_i\). This is a very general way of addressing many problems in regression and the resulting models are called generalized linear models (GLMs). Logistic regression is a very common example of GLMS but there are others, like probit and Poisson regression, which we will not cover in this course.

All GLMs have the following three characteristics: a probability distribution describing a generative model for the outcome variable; a linear model; and a link function that relates the linear model to the parameter of the outcome distribution.

The linear model can be written as follows:

\[\eta = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X_1 + \cdots + \beta_k X_k\] As was mentioned previously, logistic regression is a common GLM used to model a binary categorical outcome (0 or 1). In logistic regression, the link function that connects \(\eta_i\) to \(p_i\) is the logit function which can be written as follows. For \(0\le p \le 1\):

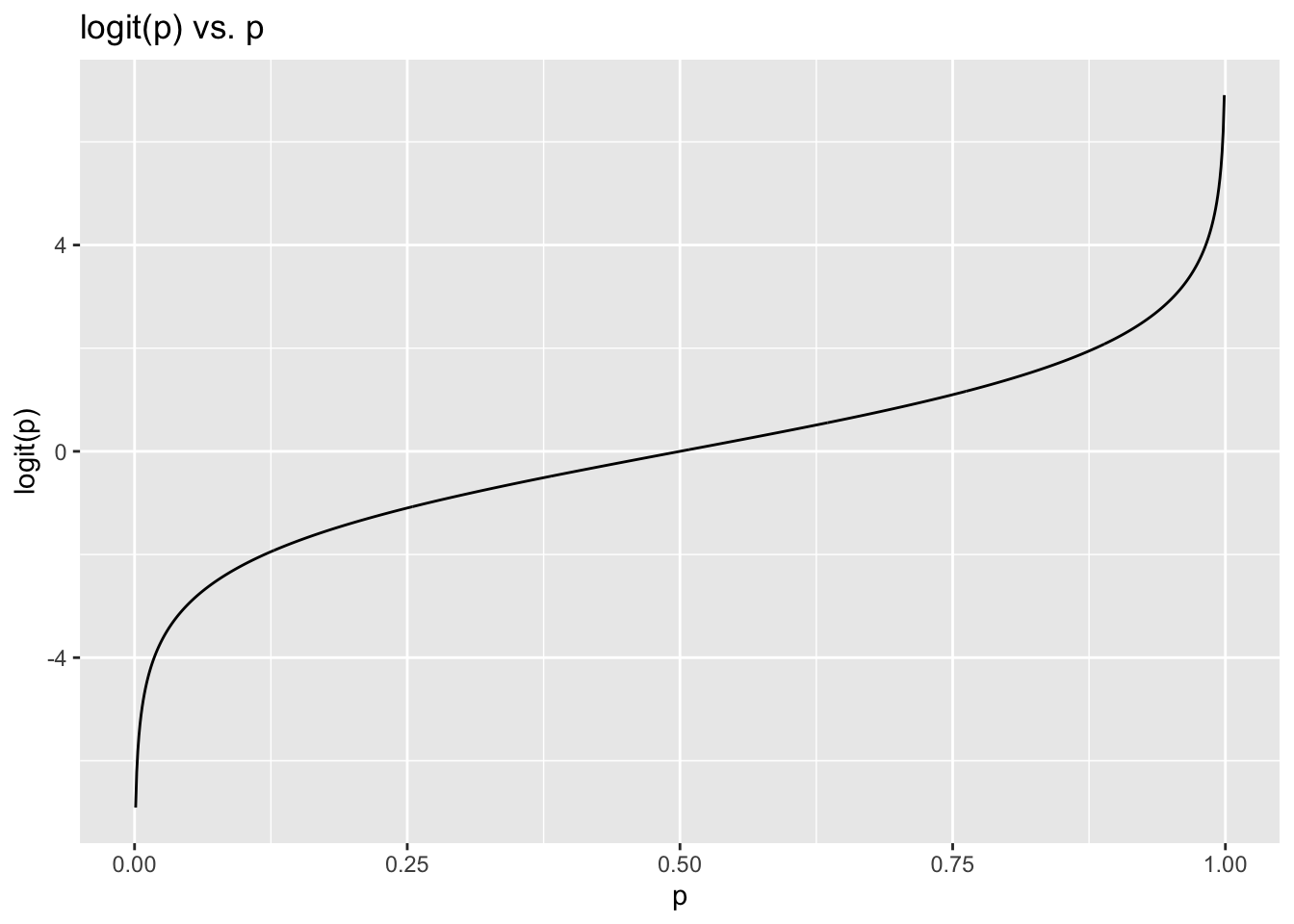

\[logit(p) = \log\left(\frac{p}{1-p}\right)\] Here is what that function looks like when we plot it:

This plot shows that the logit function is a transformation of the probability \(p\) that maps it to the real line. The logit function is useful because it maps the probability of success to the real line, which is necessary for the linear model.

Analyzing conflict onset

We can use logit models to analyze conflict onset. In this example, we will use the peacesciencer package to analyze the onset of conflict. The peacesciencer package provides a number of datasets and functions for analyzing conflict and peace. It provides data from a number of important datasets in the field of conflict studies, e.g. the Correlates of War (CoW) project, the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP), and the Militarized Interstate Dispute (MID) dataset. It also provides functions for analyzing conflict and adding control variables to the dataset.

Let’s go ahead and load the peacesciencer package and create a dataset that we can use to analyze conflict onset. We will use the create_stateyears() function to create a dataset with state-years, and then add some control variables to the dataset. We will add the UCDP/PRIO Armed Conflict Dataset (ACD) to the dataset, which provides information on the onset of armed conflict. We will also add the Polity IV dataset, which provides information on the level of democracy in each country-year. We will add the CREG fractionalization index, which provides information

library(peacesciencer)

library(tidymodels)

conflict_df <- create_stateyears(system = 'gw') |>

filter(year %in% c(1946:1999)) |>

add_ucdp_acd(type=c("intrastate"), only_wars = FALSE) |>

add_democracy() |>

add_creg_fractionalization() |>

add_sdp_gdp() |>

add_rugged_terrain()

glimpse(conflict_df)Rows: 7,036

Columns: 20

$ gwcode <dbl> 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2…

$ statename <chr> "United States of America", "United States of America",…

$ year <dbl> 1946, 1947, 1948, 1949, 1950, 1951, 1952, 1953, 1954, 1…

$ ucdpongoing <dbl> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0…

$ ucdponset <dbl> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0…

$ maxintensity <dbl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA,…

$ conflict_ids <chr> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA,…

$ v2x_polyarchy <dbl> 0.605, 0.587, 0.599, 0.599, 0.587, 0.602, 0.601, 0.594,…

$ polity2 <dbl> 10, 10, 10, 10, 10, 10, 10, 10, 10, 10, 10, 10, 10, 10,…

$ xm_qudsest <dbl> 1.259180, 1.259180, 1.252190, 1.252190, 1.270106, 1.259…

$ ethfrac <dbl> 0.2226323, 0.2248701, 0.2271561, 0.2294918, 0.2318781, …

$ ethpol <dbl> 0.4152487, 0.4186156, 0.4220368, 0.4255134, 0.4290458, …

$ relfrac <dbl> 0.4980802, 0.5009111, 0.5037278, 0.5065309, 0.5093204, …

$ relpol <dbl> 0.7769888, 0.7770017, 0.7770303, 0.7770729, 0.7771274, …

$ wbgdp2011est <dbl> 28.539, 28.519, 28.545, 28.534, 28.572, 28.635, 28.669,…

$ wbpopest <dbl> 18.744, 18.756, 18.781, 18.804, 18.821, 18.832, 18.848,…

$ sdpest <dbl> 28.478, 28.456, 28.483, 28.469, 28.510, 28.576, 28.611,…

$ wbgdppc2011est <dbl> 9.794, 9.762, 9.764, 9.730, 9.752, 9.803, 9.821, 9.857,…

$ rugged <dbl> 1.073, 1.073, 1.073, 1.073, 1.073, 1.073, 1.073, 1.073,…

$ newlmtnest <dbl> 3.214868, 3.214868, 3.214868, 3.214868, 3.214868, 3.214…Now we can use these data to analyze conflict onset using logistic regression. We will use the glm() function to fit a very basic binary logistic regression model where we predict conflict onset with GDP per capita.

The glm() function is used to fit generalized linear models, which include logistic regression models. Note that we have to specify the family argument as "binomial" to identify logit as the link function.

We will use the ucdponset variable as the outcome variable, which indicates whether an armed conflict onset occurred in a given year and country. We will use the wbgdppc2011est variable as the predictor variable, which indicates the GDP per capita of the country in a given year. Finally we will use the summary() function to summarize the results of the logistic regression model.

conflict_model <- glm(ucdponset ~ wbgdppc2011est,

data= conflict_df,

family = "binomial")

summary(conflict_model)

Call:

glm(formula = ucdponset ~ wbgdppc2011est, family = "binomial",

data = conflict_df)

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

(Intercept) -1.16241 0.42606 -2.728 0.00637 **

wbgdppc2011est -0.33082 0.05261 -6.289 3.2e-10 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

(Dispersion parameter for binomial family taken to be 1)

Null deviance: 1389.6 on 7035 degrees of freedom

Residual deviance: 1358.4 on 7034 degrees of freedom

AIC: 1362.4

Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 7To interpret the results of the model there are few things we can do. First, we can just look at the direction and significance of the coefficients, just like we would in a linear regression model. Second, we can exponentiate the coefficients to get the odds ratios. The odds ratio is the ratio of the odds of the outcome occurring in one group to the odds of the outcome occurring in another group. In this case, the odds ratio is the ratio of the odds of conflict onset occurring in one group to the odds of conflict onset occurring in another group. Finally, we can use the coefficients to calculate the probability of the outcome occurring for different values of the predictor variable.

Let’s start by looking at the coefficients of the model, namely the coefficient for log GPD per capita. Here we see that the coefficient is -0.33.

\[\log\left(\frac{p}{1-p}\right) = -1.16-0.33\times \text{logGDPpc}\]

This tells us that the relationship between GDP and conflict onset is negative - as GDP per capita increases, the odds of conflict onset decrease. But we cannot interpret the magnitude of the effect directly. For this, we need to exponentiate the coefficient to get the odds ratio. The odds ratio is the ratio of the odds of the outcome occurring in one group to the odds of the outcome occurring in another group.

If we exponentiate the coefficient, we get an odds ratio of 0.718. This means that for each one unit increase in log GDP per capita, the odds of the outcome occurring are multiplied by approximately 0.718, assuming other variables in the model are held constant.

This means that an increase in GDP per capita is associated with a decrease in the odds of the outcome occurring. The odds of the outcome decrease by about 28.2% for each unit increase in GDP per capita (on average).

Another thing we can do is calculate the probability of conflict onset for different values of GDP per capita. We can do this by calculating the predicted probabilities for different values of GDP per capita. One way to do this is to use the marginaleffects package, which calculates the marginal effects of a model for different values of the predictor variable.

Below, we calculate the predicted probability of conflict onset for different countries with very different levels of GDP–the United States, Venezuela and Rwanda. We start by selecting the data for these countries in 1999, and then we calculate the marginal effects of the model for these countries by calling the predictions() function from the marginaleffects package. Finally, we clean up the results with the tidy() function from the broom package to make them easier to interpret.

# load the marginaleffects library

library(marginaleffects)

# select some countries for a given year

selected_countries <- conflict_df |>

filter(

statename %in% c("United States of America", "Venezuela", "Rwanda"),

year == 1999)

# calculate margins for the subset

marg_effects <- predictions(conflict_model, newdata = selected_countries)

# tidy the results

tidy(marg_effects) |>

select(estimate, p.value, conf.low, conf.high, statename)# A tibble: 3 × 5

estimate p.value conf.low conf.high statename

<dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <chr>

1 0.00853 4.20e-161 0.00606 0.0120 United States of America

2 0.0141 0 0.0113 0.0175 Venezuela

3 0.0311 1.36e-250 0.0256 0.0377 Rwanda The results show that the predicted probability of conflict onset is highest for Rwanda, followed by Venezuela, and lowest for the United States. This is consistent with the idea that GDP per capita is negatively associated with conflict onset.